The beauty of bringing opposites together

Publicado originalmente en Pentatone

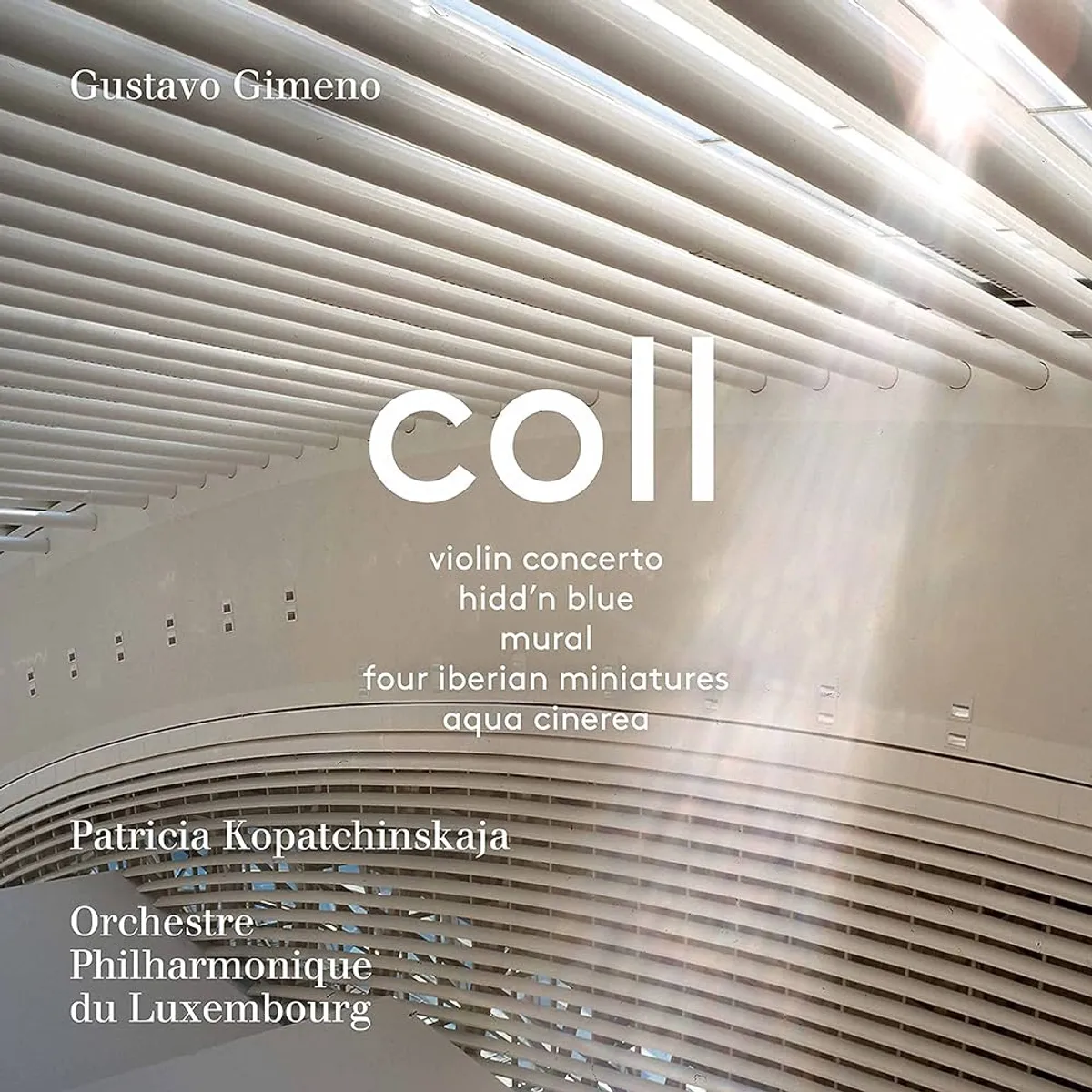

At the end of 2016, Patricia Kopatchinskaja and Gustavo Gimeno found themselves on a train on their way to a concert in Valencia. It so happened that Francisco Coll – who had left his hometown ten years earlier – had also travelled there to spend a weekend with his family. Kopatchinskaja was interested in getting to know Coll’s music, so during the journey Gimeno showed her a recording of his Hyperlude IV for solo violin. She liked it so much that she played it as an encore at her concert that very night. Since then, the collaboration between the two has continued to bear fruit: Rizoma, Les plaisirs illuminés – Double Concerto, LalulaLied and the Violin Concerto are the works that Coll has written for Kopatchinskaja in recent years, each piece demonstrating that their two personalities – as different as they are – vibrate together with a very special intensity.

In appreciation, Coll has dedicated to her his Violin Concerto, without doubt one of his most ambitious and most accomplished works. The concerto is intimately linked to the figure of Kopatchinskaja, not only because in its second movement he quotes his own Hyperlude IV – the work which brought them together –, but also because the whole piece is in a sense a portrait of the violinist: from the explosive fury of the first movement, through the sensuality of the second, to the youthful and unpredictable character of the third.

A joint commission from the Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg and Philharmonie Luxembourg, the London Symphony, the Seattle Symphony, the NTR ZaterdagMatinee and the Bamberger Symphoniker – and premiered in Luxembourg barely a month before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in Europe –, the Violin Concerto is the consummation of many of the concerns that Coll had been exploring in the previous years, regarding his relationship with the distillation of complexity and his interest in boldly taking on the problems of tradition, a process which he had begun in 2013 with Mural. But above all, the work is a constant exploration of limits and extremes. As in all his music, the instability that runs through the piece is the result of a union of opposites. And in the Violin Concerto, the past and the present converge in a single space; the superficial and the profound entry into mutual contradiction; the most delicate expressiveness melts with the most extreme violence, creating a mysterious and polymorphic beauty: excessive, perverse, closely related to decomposition, but above all, beauty as a manifestation of instability.

This attraction towards instability, extremes and the union of opposing or conflicting elements has been a constant in his work from the beginning. One of the first compositions in which he attempted to represent these contradictions was Hidd’n Blue, a short and schizophrenic orchestral overture written soon after arriving in London in 2008, right at the beginning of the financial crisis. Hidd’n Blue was premiered by the London Symphony Orchestra and François-Xavier Roth at LSO St Luke’s, and one year later was presented to a larger audience in the Barbican Hall under the direction of Coll’s mentor, Thomas Adès. Since then, it has been programmed by orchestras around the world, to the point that it has become one of his most frequently performed pieces. In it, through an accelerated narrative rhythm, a play of sonic extremes and the overlaying of different rhythmic patterns, Coll warns us of the hysteria and the contradictions of our time, showing us that all the instability present in his music is not a mere whim, but rather a kind of social portrait. However, beneath all this chaos runs a sort of illusory canon, a contaminated form of beauty which seems to want to forge a path into noise, but which at the same time is nothing more than a ghostly appearance composed of dust and residues. When one emerges from the depths of Hidd’n Blue, the image one returns with is one of blurred memory, a diffuse image, a remnant; the image in ruins. It is not possible to reconstruct the canon, perhaps because it was never actually there.

However, it was not until Mural that Coll started exploring consciously his interest in ruins. The work, which can be understood as a symphony in five movements, was commissioned jointly by the Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg and Philharmonie Luxembourg, the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain and the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía, and premiered by the first of those in 2016, also under the baton of Gimeno, to whom the piece is dedicated. If Hidd’n Blue was then an attempt to portray his present, in Mural that present enters directly into a dialogue with the past. Not for nothing was it presented by the BBC Proms as a «grotesque symphony», since in it traditional dances, quasi-tonal progressions, canons, fugues and quotations from composers of the past coexist with obsessive rhythms, scrap-metal percussion and other elements of pop culture, among many caricatures and hidden jokes. Far from being glorified in the romantic way, the fragments of tradition that appear here seem to have been salvaged out of the rubble, always with that disturbance of the contemporary on their surfaces. But just as in Hidd’n Blue or the Violin Concerto, its beauty is only possible thanks to that same residual noise that constantly destabilizes it. In Mural, Coll treats history as just another malleable material, taking its vestiges in order to build with them something completely different: a «mural» of heterogeneous images which are related to each other through a fragmentary rhetoric, and brought together by means of a unique and mysterious sense of humour.

Also illusory – and irreverently humorous – is the folkloric world of his Four Iberian Miniatures. As the piece progresses, the initial strums of a jota give way to fandango rhythms and flamenco clapping, or a strange ternary tango ends up turning into Lorca’s «Anda jaleo». The hallucinogenic, delirious quality of the universe created by Coll here is a perfect match for Kopatchinskaja’s violin: satirical and brazen, full of broken continuities, formless objects and other irrational logics that belong to a dream. While there were traces of folk elements in his music before, Coll’s real engagement with the music of his native country began in 2013 with this piece. Just like the freedom of imagination preached by the surrealists, the folklore of the Four Iberian Miniatures does not faithfully correspond to the styles of flamenco or the formal structures of the music it alludes to; it is, instead, largely invented. It is a distilled folklore, reduced to its essence, which Coll uses freely – just as he does with the ruins of tradition in Mural – to build his own universe.

The album finishes with his Opus 1, Aqua Cinerea, the work that led to his departure from Spain a little more than a decade ago. He wrote it in 2005 – with only 19 years old – and it was premiered one year later at the Palau de la Música in Valencia with Cristóbal Soler and the Orquestra Filharmònica de la Universitat de València – the orchestra in which, incidentally, Coll himself played the trombone. Coll sent the recording of that premiere to Thomas Adès, who, impressed by the maturity and freshness of his ideas, invited him to study with him in London, as his only student. Aqua Cinerea was, indeed, the beginning of everything: not just of his professional career, but also of everything he would come to explore in his subsequent works. In its pages, spontaneously and intuitively, can be found his whole world in concentrated form, poured out raw onto the paper. This is why Aqua Cinerea could be considered, in many aspects, the most vivid and genuine reflection of his personality. When writing his Violin Concerto fifteen years later, perhaps he had in mind the spirit that flows through Aqua Cinerea, because during the creative process he was constantly repeating to himself: «Don’t try to please a conservative public or the institutionalised avant-garde; just write what you hear and dare to fail.» And Coll is, certainly, an artist who, like Kopatchinskaja or Gimeno, not only can, but – more than that – dares.

(English translation from Spanish by Natalie Shea)